As a follow-up to my previous post where I psuedo-whined about common knowledge gaps in technology projects, I thought I’d try to contribute a solution to the problem. I’ll list out each of the areas that I previously posted about; the areas I think people are behind on. It’s knowledge debt. When you don’t spend the time to catch up, you’re in knowledge debt.

Troubleshooting

Troubleshooting is a learned skill and it’s hard to “train”. A lot of effectiveness in troubleshooting is related to the specific skill or expertise domain so a novice is not going to magically become effective at problem-solving just by knowing how to troubleshoot generically. Let’s instead try to focus on some specific examples and talk about common patterns and strategies. The easiest examples revolve around so-called “computer problems” which really mean desktop, networking, environmental and software corruption problems. I’ll stay away from debugging which is a much more precise process where you have the advantage of memory inspection, breakpoints and god-like control over the problem unless you hit external resources which would land you back in the “computer problems” category.

Let’s say a developer is designing a web application on their laptop. Everything works as they designed. Now it’s time to deploy to the test server for other team members to integrate/play with. Ok, let’s scp our .zip/.war/installer/.tar/whatever up to the server and then see if it works. A near-infinite list of things can go wrong but here are a few:

- You can’t scp to the server.

- If you got a network error, can you ping the server? If you can ping, can you telnet to port 22? Ping just hits the IP. Telnet will hit the IP plus the port. If the IP works and the port doesn’t then something is filtering the port (firewall) or SSH on the server is not listening on 0.0.0.0 (every interface) but on localhost or another interface.

- If you are getting a login type error after you connect then try just ssh’ing to the box first. Maybe your shell is messed up. Are you overriding the shell with WinSCP? Are you trying to start in a directory that you don’t have +x on? Maybe your account is locked. The idea here is to ignore network problems. You’ve got a socket and a login prompt. It’s OS/shell related at this point.

- Understand that putty’s configuration is not shared by WinSCP but pscp is. Try pscp’ing with the -load switch. For example pscp -load testserver-saved-sessions file user@testserver:/tmp will load the “testserver-saved-session” putty config and SCP a file named “file” to the server. If you have proxy settings or other parameters that are needed, you can use pscp instead of reconfiguring WinSCP.* The webapp won’t start.

The list of problems can go on from “the webapp behaves differently” to “you can’t get to the webapp at all”. And this is just deploying to the test environment! In any case, the common pattern should be:

- Is the problem reproducible? Is it intermittent? This answer should help narrow down the problem scope. Intermittent problems could be external, timing issues, race conditions, memory management, resource limits, functional bugs, synchronization and temporal problems like this.

- Log mentally or in a journal what each finding means. You should be thinking critically and expecting results as you try things: “if the following test does A then it means X. If it doesn’t then it means Y”. See this fantastic single-bit-flip troubleshooting session here where the author systematically dives deeper and deeper into a segfault until he proves that a system binary bit-flipped while in memory.

- Change one thing at a time.

- Try to break the problem into levels if it’s related to lifecycle or something serial. Start high-level and work lower (ie: trace the network cable before setting up debugger breakpoints). Once you’ve proved a level is working, ignore problems on that level. Unless you’re doubting your sanity, if ping works, IP is working.

- Assume it’s your code and your problem forever. When it’s not your code’s problem, assume it is. Try typing up an angry email to the author, corporation or project and blame them with vigorous detail about why you think this is their problem and not your fault. Do not send it. By the end of your rant, you might have thought of things you haven’t tested or tried enough when proposing what their problem is.

- Break down the problem and prove hypotheses. Can you break the app even more? If you fix it, can you break it again to prove your sanity?

Even though many of my examples are deployment and networking related, the same process can be used for development and software. Since so many abstraction layers exist in software, it’s very similar to a system or a network stack. Learning these troubleshooting strategies can be a valuable skill to learn and might avoid just giving up or asking a coworker for help. I’ve met people that have no domain experience in a problem area but have enough previous experience and troubleshooting skill that they seem magically able to figure out a problem (and suddenly are regarded as experts).

VNC

Understanding VNC can be difficult because many devs/admins/dbas/whatever are used to other things. Maybe they are even used to VNC but don’t understand how powerful it can be or why it’s being used in the first place. So let’s talk about the basics and maybe this will clear up what VNC is and what it isn’t.

First, VNC is cross platform and open source. That means I can use a Windows VNC client to connect to Windows, Linux, Solaris, Mac, iPhone or whatever. Open source means not so much that VNC is free but that there are many tools available because the spec is open. I can do “many-to-many” client to server. Remote desktop is Microsoft only. VNC can compress remote sessions for slow WAN links. VNC can be faster than X11 if you use it right. VNC can keep a GUI process/installer/program running while you disconnect. VNC can let you broadcast your screen to a classroom of students. VNC can let you bounce around a network when a firewall or network layout prevents you from connecting directly to a server. It’s flexible, familiar to many and open source.

Let’s talk about what VNC isn’t. VNC is an onion skin, it’s not the root window. If you move your mouse in VNC, someone who walks over to the server won’t see the mouse moving. It’s not SSH, you can’t necessarily copy files over VNC, you won’t automatically get a shell either. It’s not secure. It’s not remote desktop. It’s not X11. It’s different on Windows than it is on UNIX, UNIX lets you pick your window manager (Gnome,KDE, twm). VNC has a separate password than your OS user account.

When you start vncserver, it reads your ~/.vnc/xstartup file and launches whatever is in there and fires up a port to listen on for your user. So you can fire up multiple servers if you want but each time you do, everything in ~/.vnc/xstartup is duplicated. If you use Gnome in your xstartup, this might make Gnome mad because it’s not good at running twice.

Once you are connected to your vncserver with a client, you stay logged in. Let’s say you fire up vncserver with Gnome configured for xstartup. So your ~/.vnc/xstartup looks like this: ` #!/bin/sh

Uncomment the following two lines for normal desktop:

unset SESSION_MANAGER

exec /etc/X11/xinit/xinitrc

[ -x /etc/vnc/xstartup ] && exec /etc/vnc/xstartup [ -r $HOME/.Xresources ] && xrdb $HOME/.Xresources xsetroot -solid grey vncconfig -iconic & xterm -geometry 80x24+10+10 -ls -title “$VNCDESKTOP Desktop” & gnome-session & `

This is going to open xterm everytime your log in and you’ll have a Gnome desktop. That’s because the process stack looks something like this:

` vncserver (includes the X11 server) |– X11 Desktop (ie: Gnome as a gnome-session process) |—- vncconfig (a vnc utility dialog box app, not needed most of the time) |—- gnome-terminal (one of many windows within your vnc window) |—— bash (unix shell within gnome-terminal) `

I see people make a common mistake when using VNC. They’ll log out of Gnome instead of closing their client window. So the vncserver process lives but there’s no desktop shell. So when they log back in, they just have a blank blue (or whatever color) screen and they’re like “IT’S BROKEN!”. Look at the process stack above. If you log out of the X11 desktop (clicking System->Logout in Gnome) then your process stack looks like this: ` vncserver |– nothing `

Everything is gone now except the vncserver and X11 server which aren’t running anything interesting. So you can connect but you can’t do anything. So don’t log out with the Log Out menu. Just close the VNC client window.

VNC is really good at WAN traffic (like from home to your office). Well, you can configure it that way. There are many types of clients out there but many of them either have a preset for slow links or let you set the compression to fast crappy quality so that you can work over a WAN. From more of a CS perspective, I like to think of VNC as local CPU-hit compression and then a smaller network packet and blown up on the client side. Since you’re network-bound on a WAN, this makes this easier on the WAN and the experience is faster.

X11

X11 is called the X Server because clients actually connect to it to display GUIs like a client-server model. It’s designed this way to allow for flexible displaying of GUIs. Because X11 is a client server model, you can forward X11 over SSH for example and have X11 apps pop up on your local desktop X11 server like magic. Or you can have VNC display your apps instead, which is how the Xvnc process works and no Xorg process is needed.

So X11 on Linux kicks off in init level 5. The root window, which you’ll see if you walk over to a server, is running as the root user and will let you log in as whatever user on the box. Here’s an example process: ` $ ps auxww|grep Xorg root 3320 0.0 0.6 34220 27721 tty7 Ss+ Jun24 1:06 /usr/bin/Xorg :0 -br -audit 0 -auth /var/gdm/:0.Xauth -nolisten tcp vt7 `

From there, your desktop shell (like Gnome) is kicked off as the user you logged in as which displays back to the X server. If you kill X11 (with Ctrl-Alt-Backspace) then you lose everything within the X server. But VNC is not using the Xorg process, so you won’t kill off anyone’s VNC sessions or anything contained within them. You also won’t kill people that are forwarding X11 apps back to their laptop or what-not. Because they are running a local X11 server such as Xming or Cygwin. Because the desktop shell is running as the current user, it’s usually a bad idea to log into the console as root. It’s unnecessary. If you need root, log in as a normal user, open a terminal and sudo or su -. This will prevent you accidentally doing something bad as root with the file browser, prevent hackers from forwarding malicious apps to you (if you do a xhost + for example) and in general just a better “least privilege” habit to get into. Of course, most people just log in as root to the server because it’s easy (boo).

The DISPLAY variable. You set the DISPLAY variable to an X11 server hostname and port. If you log into the GUI console, you’ll see this:

$ echo $DISPLAY

:0.0

The :0.0 is a special value which signifies the root window. If you

export DISPLAY=localhost:0.0 and

$ gnome-terminal

Failed to parse arguments: Cannot open display:

It won’t work. You can’t unset it either. You have to set it to “:0.0” if you’re actually on the box. When you forward X11 over SSH, the variable will look like this:

$ echo $DISPLAY

localhost:10.0

X11 isn’t encrypted by design. So use SSH forwarding.

X11 can be slow. It sends the whole damn GUI object uncompresed over the network. So if you’re on a WAN, use VNC.

X11 can be buggy with Java swing. VNC can be used as a workaround.

Version control

Let’s say you’re working on a boring spreadsheet full of team members and their skills. You’ve put a lot of time into this spreadsheet and you don’t want to lose what you’ve done. At the same time, you want to completely reorganize it by skill type and seniority. Also at the same time, your boss likes to refer to your spreadsheet to see what kind of people you have available on your team. It’s going to be a lot of work to rework the spreadsheet and it’d be bad if your boss couldn’t access it if you saved a crappy/corrupt version to so you save a copy to the fileshare as “Team_Version_2.xls”.

Great. Except what does Version 2 mean? Also, if “Team.xls” is out there and “Team_Version_2.xls” is out there, which version is the “real” one? Maybe you tell your boss “just use the one with the most recent last modified date”, which is Team.xls right now. But then Rick from sales changes the font color in Team_Version_2.xls and then your boss is checking that for updates because that’s been updated last. Your boss is all confused now because he’s been checking the wrong one and he hired a bunch of DBAs that you already had. Argh! What is going on here?!

The problem is, you are trying to version control a spreadsheet using a fileshare. You’re trying to create different versions using a filename convention. This problem has already been solved using software called Version Control Software (VCS) like CVS, SVN (Subversion), Git and so on. At the very least you should be using Sharepoint if you’re in love with MS Office, if you’re on a software project, you should be using a VCS. Even if you’re using VCS, you might be using it wrong (like trying to version control with filenames inside a version control repository).

The problem is, you are trying to version control a spreadsheet using a fileshare. You’re trying to create different versions using a filename convention. This problem has already been solved using software called Version Control Software (VCS) like CVS, SVN (Subversion), Git and so on. At the very least you should be using Sharepoint if you’re in love with MS Office, if you’re on a software project, you should be using a VCS. Even if you’re using VCS, you might be using it wrong (like trying to version control with filenames inside a version control repository).

First, let me explain extremely briefly what each of CVS/SVN/Git is all about. CVS is old. SVN replaced CVS. Git is sort of replacing SVN but also changing many things along the way. SVN has the most mature toolset, Git has very few GUIs available although XCode 4 looks really nice. Short answer, at least use SVN. If you can hack it, use Git.

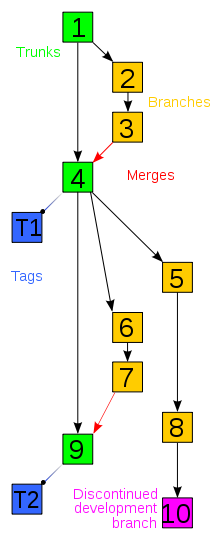

So in our example, assuming you are using SVN, you’d create a root hierarchy in SVN called ` /trunk /branches /tags /releases `

We’d commit a file under /trunk/Team.xls. This file will be the only file that anyone (like our boss) will look at for “the place to go to get our team layout”. When it comes time to make a major change, we’ll do an SVN copy to /branches/omg_major_team_reorg/Team.xls and create a branch. We’ll go to town on our branched version and make major changes. Later, when everyone has been editing the trunk version of Team.xls, we’ll merge our branched version back in and everybody’s edits will be lumped together intelligently. Recent versions of Subversion even has a diff viewer for Office docs.

So how does branching actually work? This took me a while to see when and why I’d use branching. There’s a simple diagram to the right to help visualize the process. I think it helps to just try it out a few times when you think you have a need for it and let yourself get used to the process. Without a concrete need or example, you might think it’s foreign and unnecessary. When it works for you, it’ll be more familiar and useful.

In Git, you should be branching and merging a lot. There’s a great book called Pro Git which has this and more explanation. Git really changed the way I thought about developing. I wouldn’t say I’m an expert yet. I still need to learn to commit more often and branch more. But I’m ok with these future optimization goals, I’m not ok with manual version control on a file share. :)

Sudo and cron

Sudo is a program that lets you run something as root. But more importantly, sudo can look at a file called sudoers to define a list of people and programs. You can let sally run `reboot’ or you can let dave run /etc/init.d/apache. Sudo lets you delegate to normal user accounts without everyone knowing the root password. Sudo also allows for actual, real and useful system logging. When everyone logs in as root, no one is accountable and logging is basically useless. If everyone has root and you need to find out who screwed up the server or even who is doing the most amount of good on a server, you can’t identify people because the logs will tell you that root did it and not dave or sally. So sudo allows for finer grained access control and more accountable logging. Sudo is not “su”. Also, the sudo concept is not limited to Unix. Windows Vista and 7 have UAC which is a very similar concept. UAC prompts for your password and temporarily elevates your access. They took the popup concept from OSX which actually uses Unix sudo. Ubuntu followed this design idea too. XP doesn’t have this ability and thusly, most people run as administrator all the time.

Unrelated to sudo is a scheduling utility called cron. Cron runs things at a certain time and most people get that. But there are multiple places for cron jobs to be run from. There’s a global /etc/crontab which can only be edited by root and there are individual user crontab files that normal users can edit with crontab -e. But some distros of Linux (like Ubuntu) have some special directories for cron jobs:

` $ ls -ld /etc/cron* drwxr-xr-x 2 root root 4096 2010-04-29 05:41 /etc/cron.d drwxr-xr-x 2 root root 4096 2010-06-16 15:06 /etc/cron.daily drwxr-xr-x 2 root root 4096 2010-04-29 05:21 /etc/cron.hourly drwxr-xr-x 2 root root 4096 2010-04-29 05:41 /etc/cron.monthly -rw-r–r– 1 root root 724 2010-04-14 23:51 /etc/crontab drwxr-xr-x 2 root root 4096 2010-04-29 05:43 /etc/cron.weekly `

Ok so this is pretty basic sysadmin stuff but I wanted to touch on a more important idea of cron: ETL. ETL is extract, transform and load. But don’t think in terms of data warehousing or anything specific. Think of cron and ETL as polling. Cron is stupid polling. It’s not event driven. It’s going to run whatever you say every interval you specify. If you have a “send forgotten passwords emailer” cron job set for 15 minute intervals, your users are going to be waiting up to 15 minutes for their email that lets them get into the system. This can be good or this can be a flawed design. On the other hand are events/callbacks/hooks/triggers etc. Events are smarter, more exact and better to use if you can. However integrating events all the way down to the OS layer is nearly impossible. It’s hard to ‘hook’ into an application stack from the bare OS level. Many times, polling is the only solution.

Polling vs events. Very important pattern to look out for.

Next

In the next part, we’ll wrap up with the other dearthy areas and put this topic to pasture.