Git changed the way I code singularly because of how branching works. Hopefully you have at least tried branching out in Git. Even if you have, you might still be doing the old SVN ways of never merging. If you do merge, chances are you’ve had a conflict. I have had only really bad experience with conflicts when something is majorly wrong with my repo. For the most part, Git does everything automatically and is really smart about it.

But sometimes, Git doesn’t know what’s going on because too many changes have happened. No fault of Git but sometimes it has cost me some time when I’m either doing too many things at once or did something wrong. As far as actually defining what I do and in what order (workflow), it’s not really relevant because I usually work on one feature branch at one time. In a team environment (which I haven’t really done), I’d say this looks pretty good.

Regardless, we’re going to play around with conflicts and show a sample workflow with branching. First, go into some directory you don’t care about and create a project:

cd /tmp

mkdir test_conflict

cd test_conflict

Create some “code”.

echo -e "This code computes PI and is released." > code.txt

git init

Initialized empty Git repository in /tmp/test_conflict/.git/

git add code.txt

git commit -a -m "initial commit"

[master (root-commit) e7007ea] initial commit

1 files changed, 4 insertions(+), 0 deletions(-)

Ok now we have a git repo with some code that represents our master branch. A lot of people work out of master and that’s fine but I’m going to show you how to avoid that and possibly explain why this is a good thing. First, before doing any edits, we’re going to branch master into a feature branch. This feature branch will be what we’re going to work on. Don’t name it “make_awesome” or “version2”. Name it something achievable in a small amount of time. Good names are something like “clean_up” or “try_new_library_foo”. Something specific because you’re going to create branches and merge quite a bit.

If you create two feature branches, try not to have them related. If there is common code between the two features, you probably want to avoid branching at the same time. In that case, I’d create a branch called “prepare_common” or something and try to finish the common things before starting a feature branch. This can’t work all the time and that’s ok. All you’re trying to do is avoid a nasty conflict. But if a conflict happens, it happens. We’re going to show how to recover from a conflict.

First, our customer doesn’t want our code to calculate PI anymore. They want it to write poetry. Ok, we’ll branch this change and start working on it.

git checkout -b poetry

We created and switched to a branch called poetry.

git branch

master

* poetry

While in this branch, we’re only going to work on poetry related stuff. So we’re going to change code.txt to read like this:

echo "This code generates random poetry." > code.txt

So we start some edits and commit them to git.

git commit code.txt -m "Poetry edits."

[poetry b61a83a] Poetry edits.

1 files changed, 3 insertions(+), 3 deletions(-)

But now at the same time, the customer has a bug in the PI version but we’re not done with the poetry version. They apparently don’t like PI anymore and want it to calculate Pie (the tasty dessert). Ok, let’s switch back to master and change code.txt.

git checkout master

Switched to branch 'master'

At this point, code.txt has changed back to our master version on the filesystem (talks about PI). So we edit it in master to look like this:

This code creates pie and is re-released.

Now commit.

git commit code.txt -m "Changed to pie."

# On branch master

nothing to commit (working directory clean)

Now we can git checkout poetry again and go back to working on poetry. But here’s the problem. At some point we’re going to want to merge back into master. Whether it’s now or later, doing a merge is going to raise a conflict. Do a merge now to see what I mean. Make sure you’re on branch master.

git branch

* master

poetry

Now merge the feature branch and create a conflict.

git merge poetry

Auto-merging code.txt

CONFLICT (content): Merge conflict in code.txt

Automatic merge failed; fix conflicts and then commit the result.

So now we need to see why our conflict is happening. If it’s a short list that we know we can walk through in a terminal, then just use git diff.

git diff code.txt

diff --cc code.txt

index 7216495,c3dda84..0000000

--- a/code.txt

+++ b/code.txt

@@@ -1,1 -1,1 +1,5 @@@

++<<<<<<< HEAD

+This code creates pie and is re-released.

++=======

+ I'm a poetry rewrite for a customer who is fickle.

++>>>>>>> poetry

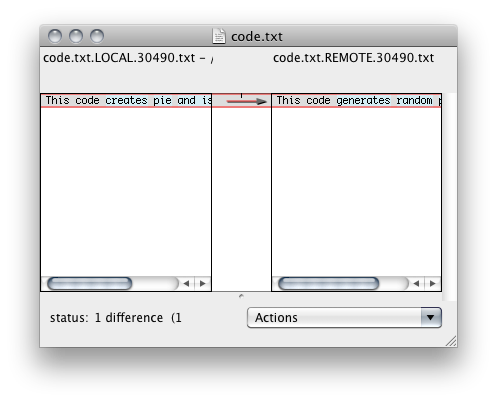

But if this text is too hard to read in a complicated project then you can use a GUI to help remind you what the changes are between the branches.

git mergetool

merge tool candidates: opendiff kdiff3 tkdiff xxdiff meld

tortoisemerge gvimdiff diffuse ecmerge p4merge araxis emerge vimdiff

Merging:

code.txt

Normal merge conflict for 'code.txt':

{local}: modified

{remote}: modified

Hit return to start merge resolution tool (opendiff):

If you hit enter, this will open a gui diff tool (FileMerge on Mac) which will let you select which left or right lines you want to use. Hit Apple+S or when you close it, select Save. In my case, I want to use the poetry branch to overwrite the entire file. So I selected the one line on the right and saved code.txt. In this case, the entire file is overwritten to look like a diff patch. Unfortunately, Apple’s tool doesn’t get rid of the .orig unless you’re really fast with selecting the side (left/right) you want and hitting Apple+S. I assume that’s because FIleMerge doesn’t capture the foreground shell’s focus. Anyway, you’ll either have a code.txt file that looks like a diff patch or you’ll have a code.txt that’s clean (if you did the FileMerge fast). In either case, we have to remove the .orig file.

rm code.txt.orig

git commit -a -m "merge poetry"

In the git log, you’ll see the commit as a normal commit. If you want to mark it, the default message will help you mark this commit as one that required a merge. In that case, don’t use -m to set the message text.

git log

commit 1cd0d5189b7d53dd1f66f6528896bc30e4a30008

Merge: e4bfa63 624e324

Author: squarism

Date: Fri Apr 8 21:50:28 2011 -0400

merge poetry

commit 830b3fac835587a79d91957c68200b74aba8a166

Author: squarism

Date: Fri Apr 8 15:23:18 2011 -0400

Changed to pie.

commit a1e68aef71421ddc8e4448c0b8d291467611843f

Author: squarism

Date: Fri Apr 8 15:23:18 2011 -0400

Poetry edits.

commit 28b83d2ae46055e2f711e86afbd9f8a61cef877d

Author: squarism

Date: Fri Apr 8 15:23:18 2011 -0400

initial commit

Notice that there’s still the pie commit in there. For a more visual idea of what’s happening here with branching, check out the great (and free) book Pro Git. It has good examples and diagrams illustrating what’s going on with branching and more advanced topics.

The following script will get you into the merge conflict state from above if you so desire:

cd /tmp

mkdir test_conflict

cd test_conflict

echo -e "This code computes PI and is released." > code.txt

git init

git add code.txt

git commit -a -m "initial commit"

git checkout -b poetry

echo "This code generates random poetry." > code.txt

git commit code.txt -m "Poetry edits."

git checkout master

echo "This code creates pie and is re-released." > code.txt

git commit code.txt -m "Changed to pie."

git branch

git merge poetry

Then you can play around with the merge GUIs and conflict states really easily. Even if you use a Git GUI like Git-Tower or GitX, it’s good to know how the branching works under the hood.